Massively standard with the general public, Edward Steichen’s 1955 documentary pictures exhibition for New York’s Museum of Trendy Artwork, “The Household of Man,” drew sharply divided crucial responses.

Some beloved the present, which sought to disclose similarities amongst various individuals in every single place, as a lot as most people did throughout an unprecedented eight-year tour to 37 nations all over the world. (9 million individuals are estimated to have seen it.) Others didn't.

From the left, French essayist Roland Barthes dismissed the massive meeting of greater than 500 images from 68 nations as “typical humanism.” From the opposite finish of the spectrum, New York critic Hilton Kramer dismissed the documentary imagery as a “self-congratulatory means for obscuring the urgency of actual issues.”

Many photographers have been dismayed. Walker Evans, a pivotal American artist within the growth of the documentary custom, which was central to Steichen’s choice, complained about “bogus heartfeeling” — a celebration of inauthentic sentimentality.

Louis Draper, alternatively, was enthralled. Nonetheless a scholar at Virginia State College, a traditionally Black college a half-hour south of his hometown of Richmond, and never but a photographer, he devoured the exhibition’s catalog. A reporter for the varsity newspaper, he quickly began taking footage. Earlier than graduating, he left and moved to New York to immerse himself within the media capital’s burgeoning photographic world.

We may be glad that he did. On the J. Paul Getty Museum, “Working Collectively: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop” is an engrossing exhibition that charts the highly effective influence of the artist, together with greater than a dozen of his colleagues. Marvelously organized by Sarah L. Eckhardt of the Virginia Museum of Superb Arts and overseen on the Getty by assistant curator Mazie Harris, it chronicles a pivotal creative growth within the second half of the twentieth century that has languished too lengthy within the shadows. Eckhardt’s lavishly illustrated catalog is great.

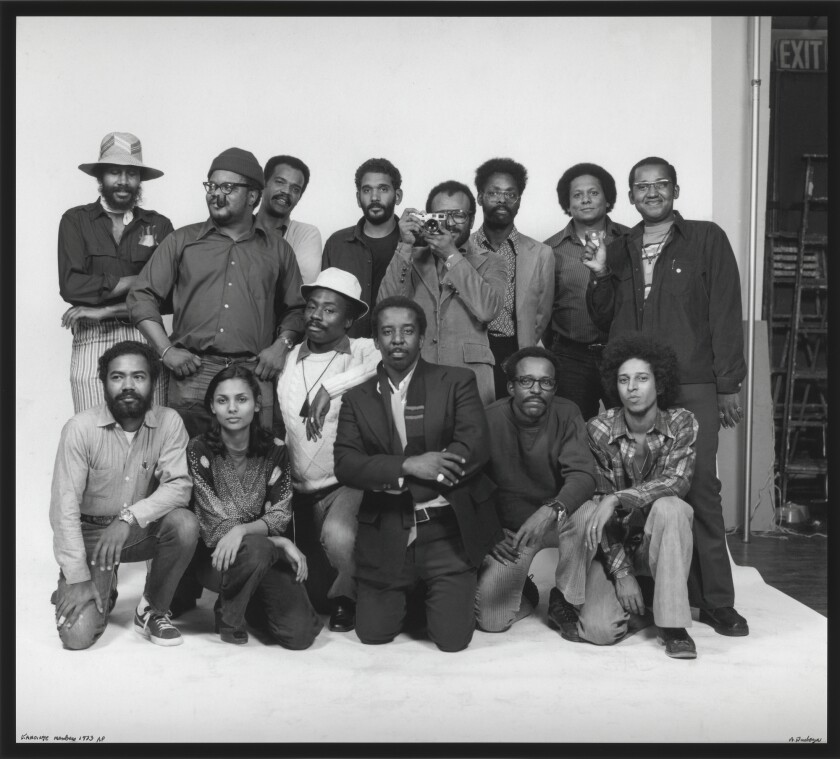

The Kamoinge Workshop is the title given to a dedicated if loosely affiliated group of 14 Black photographers, most of whom Draper rounded up in 1963. A gaggle picture made by Anthony Barboza 10 years in offers a sign of their ongoing plan: Posed in opposition to a plain studio backdrop, the artists are adjoining to a glimpse of ladders, lights and an exit signal on the proper, a pointed suggestion of productive day by day labor out on the planet.

The huge 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which gathered within the aftermath of brutal assaults on civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Ala., used the centennial of emancipation to protest entrenched racial inequality. That very same yr, the African nation of Kenya was drawing headlines because it disentangled itself from practically a half-century of British colonial incursion. The intersection between America’s personal colonial historical past and an rising African consciousness throughout the civil rights motion is enshrined within the alternative of the workshop’s title.

Kamoinge, pronounced by Draper’s group “kuh-moyn-gay,” was a phrase from Kenya’s Kikuyu individuals. Bantu pronunciations differ, nevertheless it means “a gaggle of individuals performing and dealing collectively.” The workshop was put collectively by Draper, who died in 2002, in addition to Albert R. Fennar (1938-2018), James M. Mannas Jr. and Herbert Randall. Ten extra artists quickly joined them.

A number of the Kamoinge Workshop photographers have been formally skilled within the medium, and others have been self-taught. All pursued their very own work whereas offering mutual help and encouragement. Typically, they’d get collectively on Sundays for critiques and socializing. However the one agenda was to acknowledge each their particular person autonomy as artists and their collective consciousness of Black neighborhood.

The exhibition is massive — some 200 images, all black-and-white, largely from the workshop’s first 20 years. The absence of colour displays a normal tendency within the Nineteen Sixties and Nineteen Seventies to separate images into two camps: Coloration was on the rise, however the expense and complication of manufacturing stored its use largely within the business sphere; black-and-white was for severe artwork.

Extra necessary, the flourishing commercial-image world was an antagonist that the Kamoinge Workshop sought to refute. In mass media, white perceptions of Black life dominate. These observations weren’t at all times improper, however they have been inevitably restricted, repetitive and exclusionary. The Kamoinge Workshop put disparate illustration within the foreground.

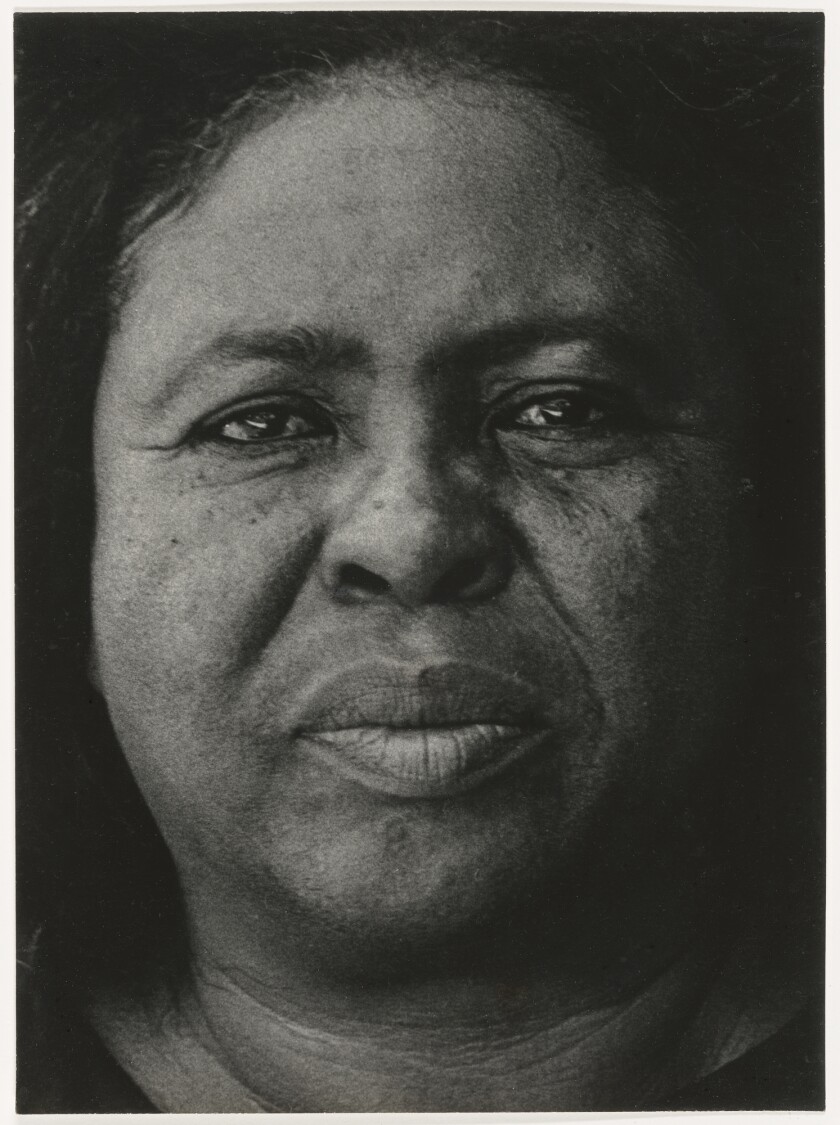

In Draper’s 1971 portrait of Fannie Lou Hamer, the face of the indomitable Mississippi voting rights activist fills the body, wanting head-on into the digicam’s lens. She’s an immovable power, not intimidating or indignant however intense and decided.

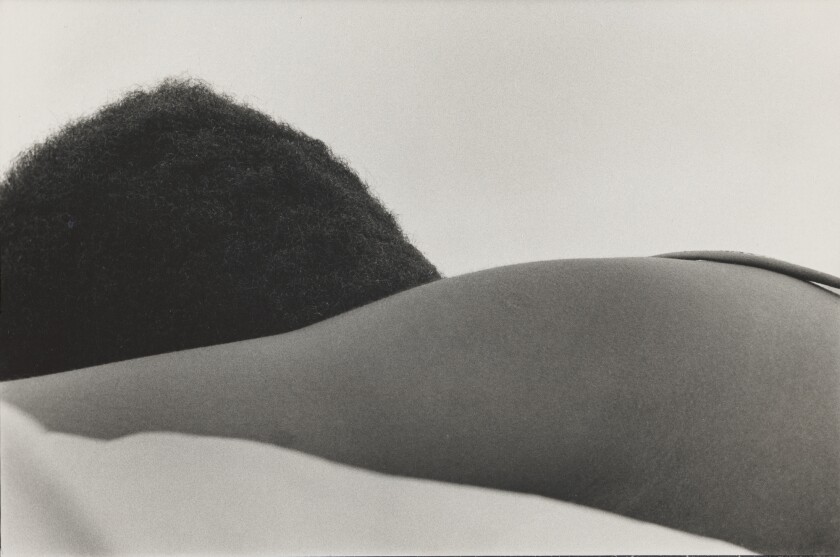

C. Daniel Dawson moved in near photograph a Black physique of indeterminate gender mendacity on a mattress, a composition in three registers from backside to prime: the glimpse of a sheet, the curving swell of a shoulder and the again of a head. An nameless however intimate determine hovers between panorama and abstraction.

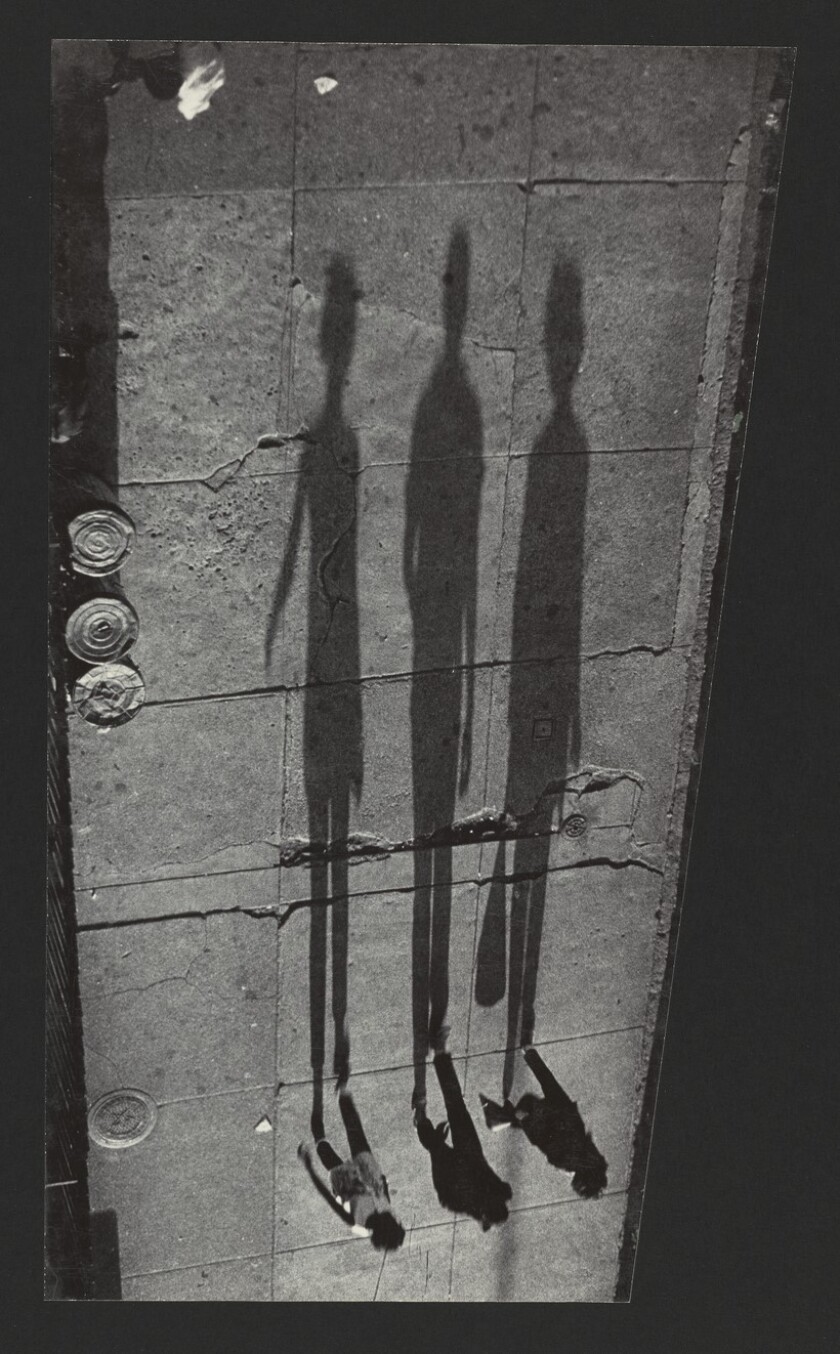

An aerial view of three individuals strolling down the road stretches their shadows from the low angle of a setting solar on the finish of the day. Adger Cowans turned the print 90 levels, the elongated shadows now rising up reasonably than spreading throughout, remodeling the trio into striding titans.

In “Pensacola, Florida,” Barboza pictured a damaged neon signal on a ramshackle constructing. On the coronary heart of the signal, the phrase “liberty” is damaged, the “e” smashed and the “r” dangling askew.

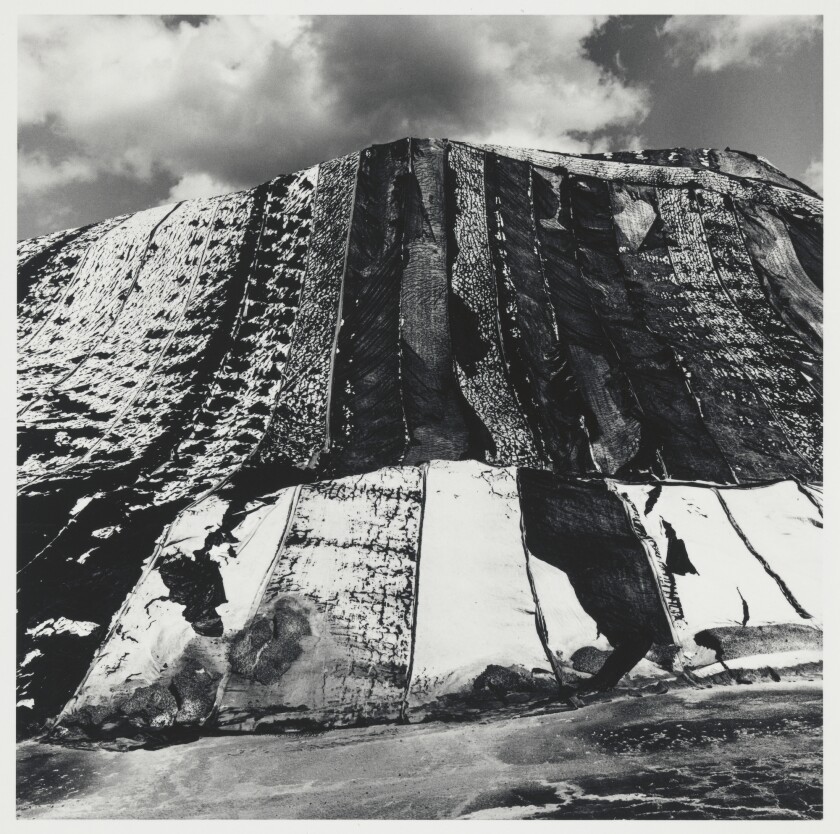

With abstraction a conflicted concern for painters and sculptors of the interval, and one which had particular hurdles for digicam work, Fennar photographed from under an infinite roadside “Salt Pile” coated in tarps. Its patterned floor provides a mysterious mountain of summary shapes beneath mild, floating clouds.

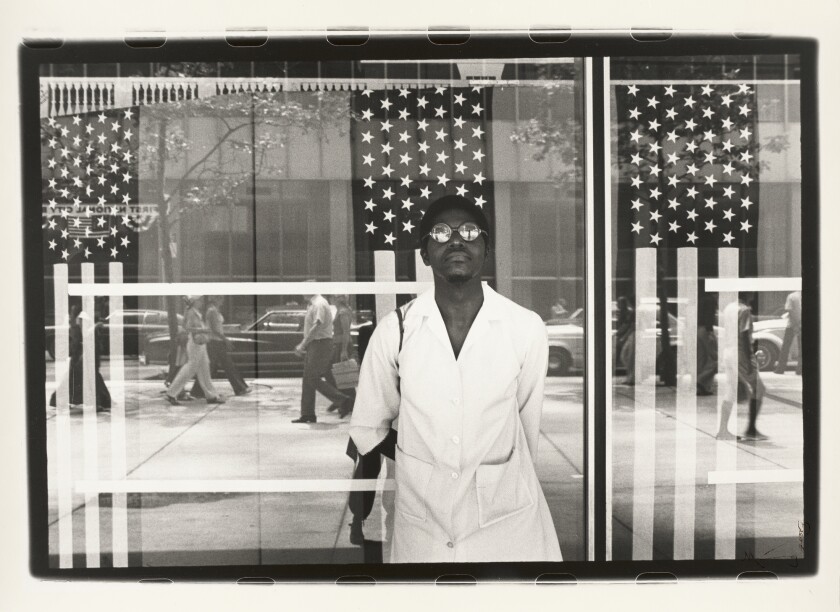

“America Seen By means of Stars and Stripes, New York Metropolis, New York” is a layered visible collage of dizzying areas by Ming Smith. A person in a white lab coat stands along with his arms behind his again earlier than a glass workplace constructing entrance, his mirrored sun shades reflecting what’s in entrance of him — together with what seems to be the artist — as absolutely because the window displays city passersby and parked automobiles on the road behind the photographer. Woven into the random, free-floating exercise, hanging American flags or banners behind the glass window present each agency construction and a way of confinement.

These aren't photographs of Black life as brutal, demoralized and fraught. Nor are they sunnily promotional. As an alternative, a easy dignity to which any particular person is entitled is the visible baseline; illuminating human expertise in America is the aspiration.

What the Kamoinge Workshop was up in opposition to is revealed in a disturbing show case, which holds the notorious cowl of Newsweek from Aug. 3, 1964, following riots in Harlem, N.Y., after an off-duty white police officer had shot and killed an African American teenager on Manhattan’s Higher East Facet. The journal’s white photographers wouldn't enterprise into the chaos uptown, and no Black artists have been on employees for instance the upcoming story. Freelancer Roy DeCarava, at this time probably the most celebrated of the Kamoinge photographers, was employed to offer an acceptable picture.

DeCarava requested workshop colleagues Ray Francis (1937-2006), Shawn Walker and Draper to pose, and he shot their unsmiling visages in close-up with their heads in a syncopated row, virtually just like the stone presidential faces arrayed throughout Mt. Rushmore. When the journal got here out, nevertheless, the photograph had been sharply cropped, the misleading headline “Harlem: Hatred within the Streets” emblazoned under it. The archetypal white concern of the indignant Black man was splashed throughout newsstands and dropped into mailboxes from coast to coast. DeCarava, who died in 2009 at 89, refused assignments from Newsweek for the rest of his life.

The Kamoinge Workshop merged two creative legacies inside the distinctive context of an oppressed minority neighborhood. Conventional African artwork represents a social venture, whereas American modern artwork embodies a extra solitary pursuit, with the artist at work alone within the studio and darkroom. Not the whole lot was ideally suited. Smith, for example, was the lone lady within the group, and she or he didn’t be part of till practically a decade had handed. The informal sexism of the period is simple.

However so is the ability of the artwork that the photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop produced. Draper productively devoured “The Household of Man,” and this present and its catalog have insightful and generally surprising classes to study and pleasures to supply. And “bogus heartfeeling” is nowhere to be discovered.

'Working Collectively: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop'

The place: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Heart Drive, Brentwood

When: Open Tuesdays by means of Sundays, by means of Oct. 9

Admission: Free; parking $10-$20

Information: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

Post a Comment