The small, unassuming wall reduction on the entrance to “Confluence,” a modest however well timed exhibition at Monitor 16 on the theme of water points associated to the Los Angeles River, seems to be emblematic of what follows.

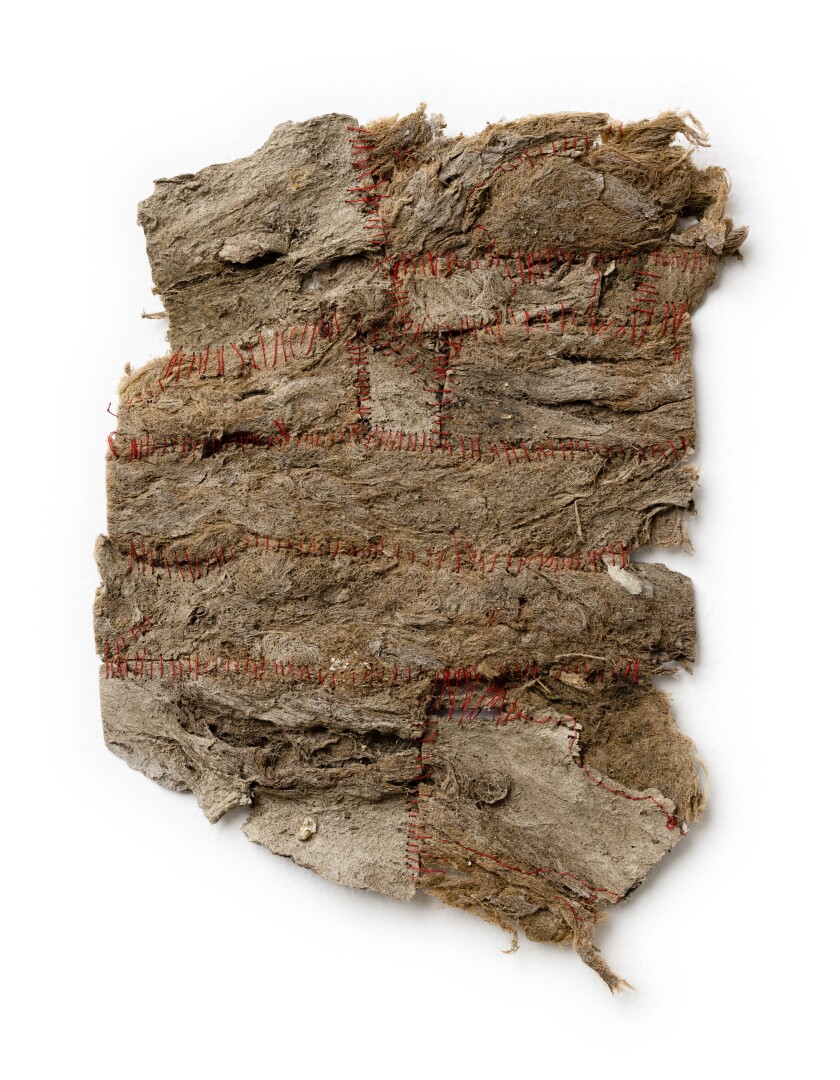

For “L.A. River Paper,” artist Emma Robbins gathered slight fragments of matted algae, leaves and fowl materials from the water, then stitched the fuzzy items along with reddish thread into an irregularly formed sheet. That is handmade paper that merges pure formation and creative intervention — a confluence, in different phrases. The phrase describes each the final means of separate issues coming collectively and — notably — the precise junction of two rivers.

What's the different river coursing by Robbins’ “L.A. River Paper”? A compelling video by AnMarie Mendoza suggests a provocative reply: a river of humanity.

“The Aqueduct Between Us,” a 39-minute oral historical past, options water photographs across the metropolis, together with pure streams; the concrete flood-control channel that runs from the San Fernando Valley to the ocean; the elegant fountains in entrance of the smooth Division of Water and Energy constructing, the 1965 downtown landmark designed in a company worldwide fashion by A.C. Martin and Associates that's excessive on any checklist of nice fashionable structure; and sections of the century-old engineering marvel that's the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Stitched collectively, they image the important liquid basis for human existence within the metropolis.

And, not so by the way, for slow-moving wreck.

Nearly your entire state of California is now ranked as experiencing extreme, excessive or distinctive aridity, the three worst ranges charted by the Nationwide Drought Mitigation Heart on the College of Nebraska. We aren’t simply in a drought, we’re in a megadrought.

Water imagery within the video is interspersed with quick, pithy interviews with quite a few Indigenous residents, largely Tongva and Paiute. “Water is life,” they repeat — a easy, imperishable refrain that resounds in opposition to the greater than 20 years of Southern California drought that's steadily constructing towards epic catastrophe. In Mendoza’s marvelously incisive video (additionally out there on YouTube) the close to invisibility of Indigenous individuals at this time in a spot the place genocide was launched greater than 175 years in the past merges with the standard inconspicuousness of vital water points from metropolis dwellers’ each day consciousness.

“Confluence” was ably organized by artist Debra Scacco, whose contribution is a drawing created from ink and water. Its summary, marbled linearity consists from an interplay with wind, which moved the liquid supplies round on the sheet till they dried. Like Robbins’ paper, it’s certainly one of a number of works that activate associated actions between artist and pure forces.

Lauren Bon assumes a not dissimilar strategy in a composition fashioned from an evaporated puddle of rainwater on a sheet of black foil. The whitish residue leaves a mottled imprint. Round and noticed markings evoke a sky map — loosely, the place the place the rain got here from.

Bridget DeLee’s “InBetween” likewise crosses territories. Suspended horizontally from the ceiling, the bottom of a palm leaf (referred to as a crownshaft) is punctured by lengthy braids of black artificial hair, that are held in place by wood pony beads. The trendy strands maintain up a second leaf suspended beneath the primary, then cascade by it to the ground. The leaves and the braids create an intersection of crowns, one naturally occurring and the opposite culturally produced.

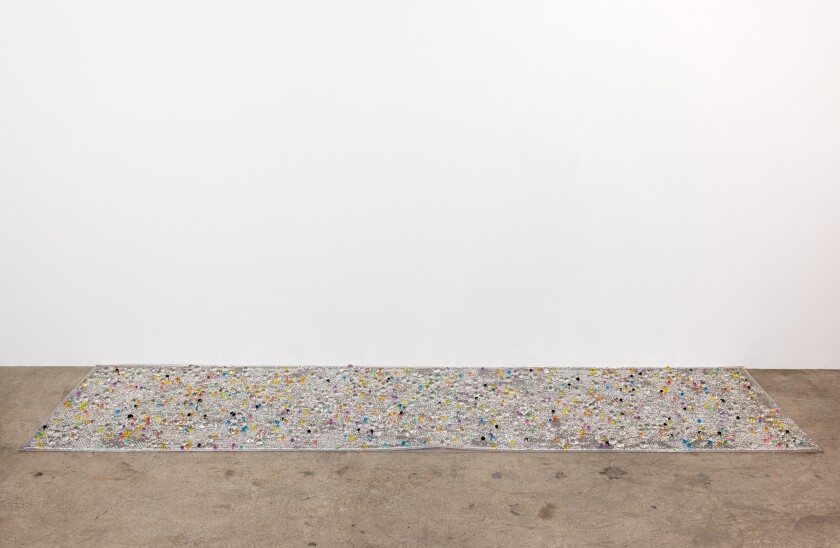

Kori Newkirk, certainly one of two males among the many present’s 9 artists, soaked super-absorbent polymer beads, the sort utilized in vases to maintain floral preparations from wilting, in river water, then unfold them in a skinny layer atop a transparent vinyl sheet unfold out on the ground. The moisture is slowly evaporating from the beads because the present continues, leaving intertwined bits of shifting sediment behind — a river-made Pollock drip portray, because it have been.

In Newkirk’s flooring piece, colour appears to have been leeching out of the polymer beads as they dry up. Elsewhere, a normal absence of colour marks these works, which depend on impartial tones. The absence is itself a residue, the stays of a longtime custom that has put aside colour’s irrational pleasures to suggest seriousness in artwork ever since Conceptualism emerged into prominence within the Seventies.

Fragments of colour do flip up entangled within the supplies of Blue McRight’s “Night time Dive,” a suspended assemblage of ropes, pulleys, a chunky metallic hook and incongruous plastic netting and hair-scrunchies woven into ornamental tiers. It’s like a sculptural salvage-job after trawling by a sludge of ocean detritus — festive streamers recovered from waste.

And colour is after all integral to Lane Barden’s fascinating grids of documentary aerial images, which seem to have been shot from a drone. His pair of grids begins on the higher left with a vivid inexperienced athletic discipline within the San Fernando Valley and, image by image, follows the contested river’s circuitous city path by 4 dozen aerial photographs, which lastly empty into the cerulean Pacific Ocean on the decrease proper.

The first exception, although, is Alicia Piller’s entrancing “Extinctions,” a sculpture whose palette of crimson, white and blue is clearly not unintentional. The central ingredient is a toy-like wood rifle jammed upright by a shark’s gaping skeletal jaw. Layered strips of vinyl and leather-based drape from the highest, which is roughly the peak of a standing particular person, bunching into turbulent swirls across the backside. The textiles, dotted with human tooth and flaccid balloons, are embalmed in clear, glistening resin that holds all of it in place.

Piller works from materials accumulations of cast-off stuff, and her composition swings between microscopic and macroscopic in a fashion loosely paying homage to Elliott Hundley’s work. The rifle, pointedly described within the object’s checklist of supplies as colonial in fashion, glances off Native American genocide; the shark’s jaw ricochets off ongoing ocean annihilation, with greater than 1 / 4 of these fish presently going through eradication, in keeping with the World Wildlife Fund. Whereas Los Angeles staggers by its driest 23-year interval in 1,200 years, the sculpture is a disconcertingly festive maypole that's concurrently brutal and unhappy.

All shouldn't be misplaced. Placing the sculpture’s title, “Extinctions,” within the plural provides a queasy sliver of future continuity. As they are saying, the Earth doesn’t a lot care about local weather change, as it should merely slough off humankind and proceed on its approach. Megadrought be damned.

'Confluence'

The place: Monitor 16, 1206 Maple Ave., No. 1005, Los Angeles, CA 90015

When: Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m. to six p.m. and by appointment.Closed Sunday - Tuesday.

Data: (310) 815-8080, track16.com

Post a Comment