When it was first revealed in 1990, Mike Davis’ “Metropolis of Quartz” hardly appeared a candidate for bestseller standing.

There was its writer, for starters. Davis was a Marxist city scholar whose main contribution to the general public discourse on the time consisted of a little-read e-book concerning the historical past of labor within the U.S., together with dispatches on associated topics within the LA Weekly and the New Left Assessment.

There was additionally the e-book itself. Launched by the lefty publishing home Verso, it was 462 dense, unsparing pages concerning the methods during which highly effective pursuits in Los Angeles — specifically, actual property builders, aided and abetted by politicians and the Police Division — had ruthlessly molded the panorama of the town to their whim, principally on the expense of the working class and other people of shade, all whereas selling myths about yard dwelling.

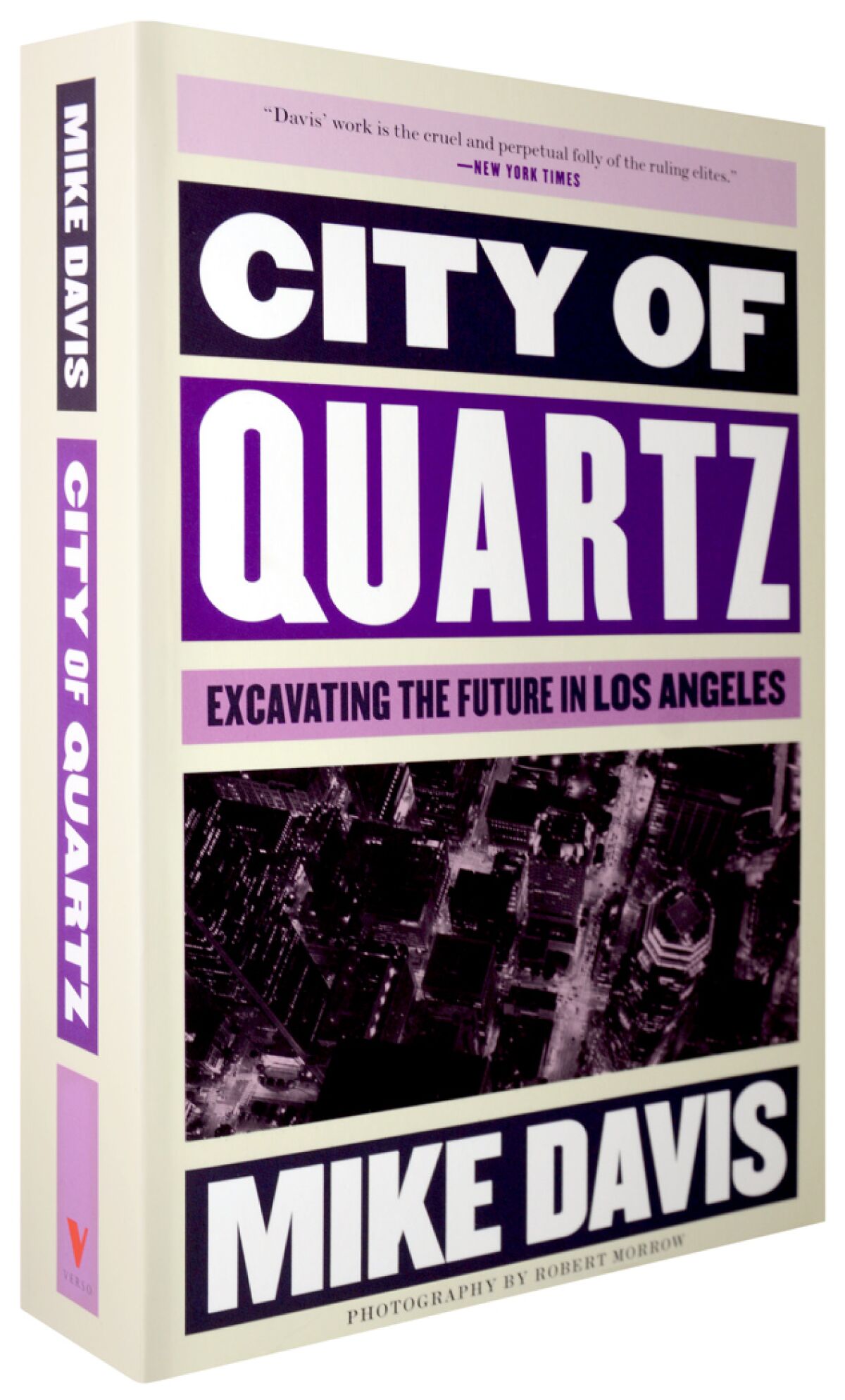

“Metropolis of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles” was nearly irrationally bold. The e-book contained a kitchen sink’s value of subject material protecting the design of company superblocks, cul-de-sac NIMBY-ism and the continued faceoff between the cultures of boosterism and noir, buttressed by copious footnotes and references to Marxist theorists corresponding to Antonio Gramsci and Herbert Marcuse. And its cowl? A looming picture of the Metropolitan Detention Middle in downtown Los Angeles by photographer Robert Morrow.

But “Metropolis of Quartz” rapidly materialized on bestseller lists when it debuted. As reporter Susan Moffat wrote in The Instances in 1994, Davis’ work “managed to show native zoning battles into revolutionary excessive drama.”

It additionally turned Davis right into a public mental. His visions of the town’s “spatial apartheid,” as described in “Metropolis of Quartz,” had initially been chided as apocalyptic by some critics. However the 1992 uprisings, which left swaths of L.A. in cinders, confirmed that his evaluation had been prescient.

Many years later, in a 2020 podcast interview with Los Angeles critic and scholar David Kipen, Davis nonetheless appeared a bit baffled by his work’s success. “I used to be completely shocked that anyone bothered to learn this e-book,” he stated.

“Metropolis of Quartz” wasn’t simply learn, nonetheless. It was devoured.

“If you choose the work of any person, it’s what the work itself did, the methods it makes us suppose in a different way,” stated historian William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “Equally essential: What number of ships did it launch? And ‘Metropolis of Quartz’ launched so many ships — whether or not it’s dissertations or conferences or articles.”

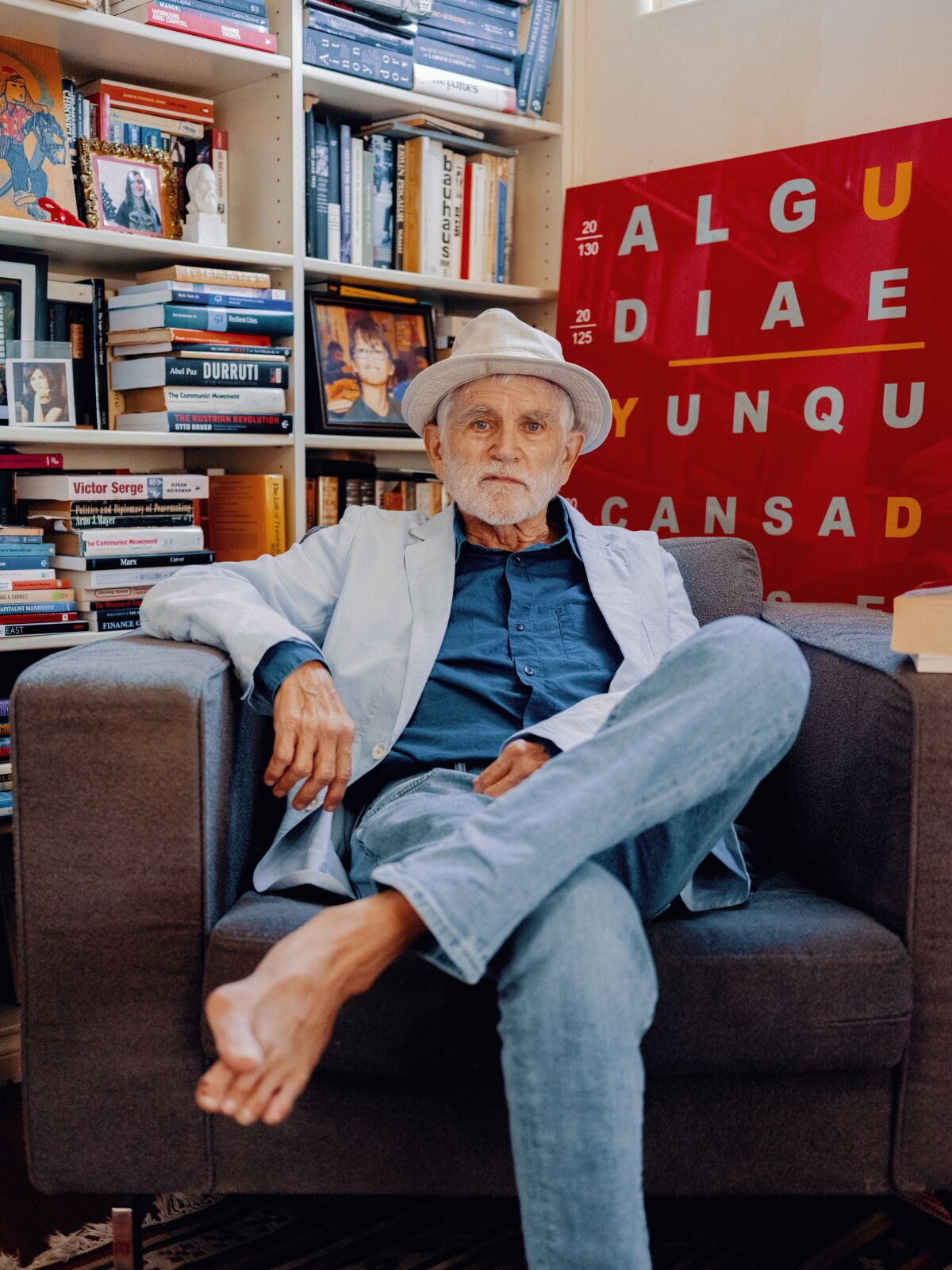

Davis, a author whose work uncovered L.A.'s social fractures and disquieted its most ardent boosters, and whose mark on the mental historical past of Southern California stays indelible, died Tuesday at his dwelling in San Diegofrom issues associated to esophageal most cancers, in accordance with his daughter and literary agent Róisín Davis. He was 76.

In an interview with Instances reporter Sam Dean in July, he accepted his terminal prognosis however stated he had hoped for a extra dramatic ending. “If I've a remorse,” he stated, “it’s not dying in battle or at a barricade as I’ve all the time romantically imagined — you recognize, preventing.”

Davis is survived by his fifth spouse, artist, curator and scholar Alessandra Moctezuma, their twin youngsters, James and Cassandra Davis, in addition to two youngsters from Davis’ earlier marriages: Jack and Róisín Davis.

Although greatest recognized for “Metropolis of Quartz,” Davis wrote greater than a dozen notable books over his greater than four-decade profession, together with 2020’s “Set the Night time on Fireplace: L.A. within the Sixties,” which he co-wrote with historian and journalist Jon Wiener. In true Davis model, it’s a radical work — 800 pages — and a profound examination of ’60s activism in a metropolis that had typically been written off as apathetic throughout that period. Critic Jeff Weiss, who edits TheLAnd, described it as “a love letter” to “the concept of collective battle.”

Extra polemical was “Ecology of Worry: Los Angeles and the Creativeness of Catastrophe,” launched in 1998, about how the town’s city design was exacerbating fireplace and drought. It additionally, fairly famously — or, fairly, infamously — featured a chapter titled “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” arguing towards deploying huge public sources to save lots of an space the place “nouveaux riches” had constructed “with scant regard for the inevitable fiery consequence.”

D.J. Waldie, the mild-mannered essayist behind “Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir,” wrote in his evaluate of “Ecology of Worry” that the e-book offered “a imaginative and prescient so dismal that it’s finally paralyzing.” Jill Stewart, a columnist for New Instances Los Angeles, described the writer as a “city-hating socialist.”

And there was Brady Westwater (actual title: Ross Ernest Shockley), a Malibu actual property agent and beginner historian who took it upon himself to fact-check Davis’ work and ship his voluminous findings to only about any journalist inside attain of a fax machine. A few of the errors chronicled by Westwater and others have been trivialities, however additionally they turned up bent truths: L.A. media and meteorologists weren't, as Davis claimed, conspiratorially taking part in down the occasional tornadic storms that touched down within the metropolis.

The Instances adopted up with a 5,600-word front-page story, during which reporter Ted Rohrlich fact-checked a number of dozen claims in Davis’ books. His view: “Most of his stretchers seem like the results of haste, wishful considering and a style for entertaining hyperbole fairly than malice.”

In response to that epic piece, Wiener wrote a letter important of The Instances. “If you happen to put the identical sources into checking footnotes in different books, you'll discover related ‘minor’ errors,” he wrote. “So how come The Instances centered on social critic Davis, as an alternative of, say, on a voice of the institution like Henry Kissinger?”

The brouhaha finally did little to shake Davis’ mental standing, nor did it undermine a few of the larger factors he was making concerning the methods energy and coverage form cities.

“That's the level with Davis: extra theoretician than historian, extra intuition than analysis,” wrote the late journalist and L.A. River activist Lewis MacAdams. “The purpose is much less what he discovers than which elements of the report he chooses to have a look at. Everyone is aware of that Malibu burns; it was not till Davis that anybody stated, ‘Let it.’ Those that argue together with his info should nonetheless grapple together with his argument.”

If “Metropolis of Quartz” was an unlikely bestseller, then Davis was an unlikely mental star.

He started his profession not in academia however as a truck driver for his uncle’s wholesale meat firm outdoors San Diego. The picture of working-class powerful was one he deployed to nice impact. His writer picture for “Metropolis of Quartz” exhibits him scowling beneath a flattop, arms folded protectively throughout his chest, a bit of brutalist city infrastructure as backdrop.

This, alongside together with his dour view of cities, led to some funereal descriptions of Davis within the press, the place he was dubbed L.A.'s “darkish prophet” and the “poet laureate of pessimism.” The French each day Le Monde as soon as baptized him a “prophète de malheur” — prophet of misfortune.

But when his public persona appeared foreboding, his persona wasn’t. A beneficiant scholar and mentor, Davis was at dwelling in all worlds, conferring with feminist theorist Susan Faludi one minute and a former Crip chief the subsequent. Within the ’90s, he held common gatherings at his Angelino Heights dwelling the place neighborhood activists just like the late Levi Kingston would cross-pollinate with rising younger essayists corresponding to Lynell George and Rubén Martínez.

He was instrumental in supporting younger writers, particularly younger Black and Latino ones. He inspired George to publish “No Crystal Stair: African-People within the Metropolis of Angels,” her assortment of observations about Black L.A. within the aftermath of the ’92 uprisings.

“When he stated, ‘It is best to do that e-book,’ I felt I wasn’t prepared,” George stated. “He stated, ‘No, you’re prepared.’” He then helped set her up with a e-book contract.

George stated Davis’ most essential legacy, nonetheless, stays the paradigm shifts he helped put into movement.

“He shifted the dialog,” she stated. “We have been lastly speaking about L.A. not in relation to New York, however Los Angeles as Los Angeles.”

Michael Ryan Davis was born onMarch 10, 1946, in Fontana, considered one of three youngsters of working-class dad and mom from Ohio (his father was a meat cutter) who hitchhiked to California in the course of the Nice Melancholy. When Davis was a younger boy, his household relocated to Bostonia, a tiny hamlet in San Diego County on the outskirts of El Cajon.

As an adolescent he held conservative views: “Proper-wing, ultra-patriotic,” he as soon as instructed a newspaper reporter. And that was when he was really desirous about politics. As a youth, he stated, he was extra preoccupied with “stealing automobiles a bit, making an attempt to pull race and stepping into hassle.” He was, he instructed The Instances in 1994, “just about your common redneck 16-year-old.”

However a sequence of formative occasions would change his worldview — and, finally, the course of his life.

In highschool, Davis grew to become intrigued by “Hiroshima,” journalist John Hersey’s account of the atomic bombing of the Japanese port metropolis throughout World Warfare II. Throughout this similar interval, a cousin who was married to a Black civil rights activist took him to an indication in downtown San Diego. There, as Davis later recalled in a 1997 interview with the journal Lingua Franca, “A gaggle of redneck sailors drenches us with lighter fluid, and one of many guys began flicking his lighter.”

There have been additionally the shifting circumstances of his household life. When Davis was 16, his father suffered a “catastrophic coronary heart assault,” an occasion that rattled the household financially. Out of necessity, he took a semester off from college to drive a supply truck. The gig supplied a wanted paycheck. It additionally launched him to the politics of labor and Marxism.

Over the subsequent 20 years, Davis lived an intensely peripatetic life, intertwining intervals of labor and research with journey and activism.

He attended Reed School in Oregon briefly, lasting solely a few weeks earlier than getting thrown out for dwelling in his girlfriend’s dorm. That stint, nonetheless, related him with the left-leaning College students for a Democratic Society, and he grew to become the group’s first regional organizer in Southern California. The expertise was important to cultivating his activist streak. Later in life, nonetheless, he expressed disappointment with the coed motion. “The New Left weren’t heroes,” he stated. “We misplaced. The civil rights guys have been the true heroes.”

By the tip of the ’60s, Davis had not solely joined the Southern California Communist Social gathering, he was operating its Los Angeles bookstore. (His FBI file, by one estimate, exceeded 100 pages.)

Principally, he made ends meet as a big-rig driver, delivering Barbies for an L.A. wholesaler. For a time he additionally drove a Grey Line bus, hauling vacationers to picturesque L.A. websites such because the Fairfax Farmers Market, all of the whereas sneaking in particulars about grim historic occasions corresponding to the Chinese language bloodbath of 1871.

By the mid-’70s, Davis was again at school, learning historical past and economics at UCLA courtesy of a scholarship from a butchers union. After receiving his bachelor’s diploma, he started coursework for a doctorate however by no means earned it. As a substitute, he relocated to Scotland, Eire, then London, the place for half a dozen years within the ’80s he served as editor of the New Left Assessment.

He returned to Los Angeles in 1987 — to a metropolis, as he instructed Moffat, that “had modified past recognition.” He resumed truck driving however a scarcity of unionized jobs meant worse hours and decrease wages. “I felt like a sharecropper on the interstate,” he later stated.

He took quite a lot of educating jobs at native schools — although, with out a doctorate, his choices have been restricted. And he started to work in earnest on the manuscript for “Metropolis of Quartz,” which introduced collectively concepts he had been cogitating on for years.

The e-book catapulted Davis into the stratosphere. He was a finalist for a Nationwide E book Critics Circle Award the yr it was revealed. Different honors and educational residencies adopted. In 1998, he acquired a MacArthur fellowship, the so-called genius grant.

“Metropolis of Quartz” is usually cited as considered one of a cluster of extremely influential books on Los Angeles and its environs. Since its preliminary publication, the e-book has been launched in three English-language editions and translated into seven different languages.

In his evaluate within the New York Instances, the late USC journalism professor Bryce Nelson in contrast the “Metropolis of Quartz” writer to “Nathanael West at his most somber.” Davis, he added, “presents a darkish, nearly unrelievedly oppressive image of life in a troublesome, hardhearted metropolis.”

Martínez, a journalist and a professor of literature at Loyola Marymount College, who has written on Davis’ private and professional legacies, first met the writer after they have been each at LA Weekly within the late Eighties. He stated those that see solely darkness in Davis aren’t studying very deeply. “There may be humor throughout his work,” he stated. “It’s a darkish humor, nevertheless it’s humor.”

Certainly, to comb “Metropolis of Quartz” is to repeatedly stumble into Davis’ barbs. Early civic booster Charles Lummis was “a malarial journalist” from Ohio. Yuppies are positioned into an invented scientific taxonomy known as “homo reaganus.” The structure of Bunker Hill is dismissed as “a Miesian skyscape raised to dementia.”

“I’m not a author’s author in any respect,” he instructed The Instances’ Dean, “however I'm a rattling good storyteller.”

All through his profession, Davis used darkness and humor (and significant principle) to color a posh image of Los Angeles. “It’s not all apocalyptic,” Martínez stated. “It may be a cautionary story, nevertheless it’s on the service of a hopeful undertaking.”

As Davis as soon as instructed a author for Salon: “I really like Los Angeles. How will you not see that? I suppose the e-book is, in the long run, a failure if it betrays not one of the sense of deep feeling I've concerning the metropolis. However that’s the place being a radical is available in — you must rain on the parade.”

Post a Comment